Imagine encountering a dodo bird in the year 2023. You’d be pretty confused, right? Well, that’s what happened in 2000 when Flora and Fauna revealed that the Siamese crocodile, a species thought to be either nearly extinct or entirely gone throughout the 1990s, was still around. Though it seemed like all hope was lost, we now have a chance to save the Siamese crocodile before they’re lost forever.

Every day, Greater Good Charities’ works hard to protect animals who are in peril, threatened, endangered, and close to extinction; now, we’re featuring a special animal on our website every month! Our planet is filled with so many wonderful creatures that need your help. From the Asian elephant to the Florida manatees, our animal neighbors are in peril. Learn more about our efforts to defend the wild and the amazing animals we’re fighting for in our monthly Species Spotlight.

Already thought to be extinct once, the Siamese crocodile is among the most endangered species of crocodile. Poaching and illegal collection of crocodile eggs, habitat loss, and incidental capture with fishing gear threaten their already small numbers every day. There are only an estimated 500 to 1,000 mature Siamese crocodiles left today, and they have been pushed out of 99% of their former habitat.

Because most conservation efforts for the Siamese crocodile are relatively new, we still have a long way to go in researching and protecting this endangered species. That's why this June, Greater Good Charities is sending their Global Discovery Expeditions program to study key ecosystems at the Sao La Nature Reserve in Vietnam. This region is a globally recognized key biodiversity area in the He province on a northern flank of mountains that are part of the Annamite Mountain chain.

As you would expect, the Siamese crocodile is covered in green and scaly. Their color allows them to blend in with murky water and forestry, and their thick coat keeps them safe. This species of crocodile is considered medium-sized, with the largest recorded crocodile reaching 13 ft and 770 lbs. You can tell the Siamese crocodile apart from other crocodiles from the four large scales on their neck, their large snout, and the bony crests behind their eyes.

Despite their scary size and appearance, the Siamese crocodile is not aggressive. In the last hundred years, only 3 to 5 Siamese crocodile attacks on humans have been reported. Throughout the regions where they live, humans often reside alongside them and utilize the same waterways they call home.

One of the great mysteries about the Siamese crocodile is the nature of their burrows. This species of crocodile excavates the banks of waterways and shares their burrows with other members of the species. We still have no idea what the burrows are for or how they evolved to build them. Research is desperately needed for us to better understand their species overall.

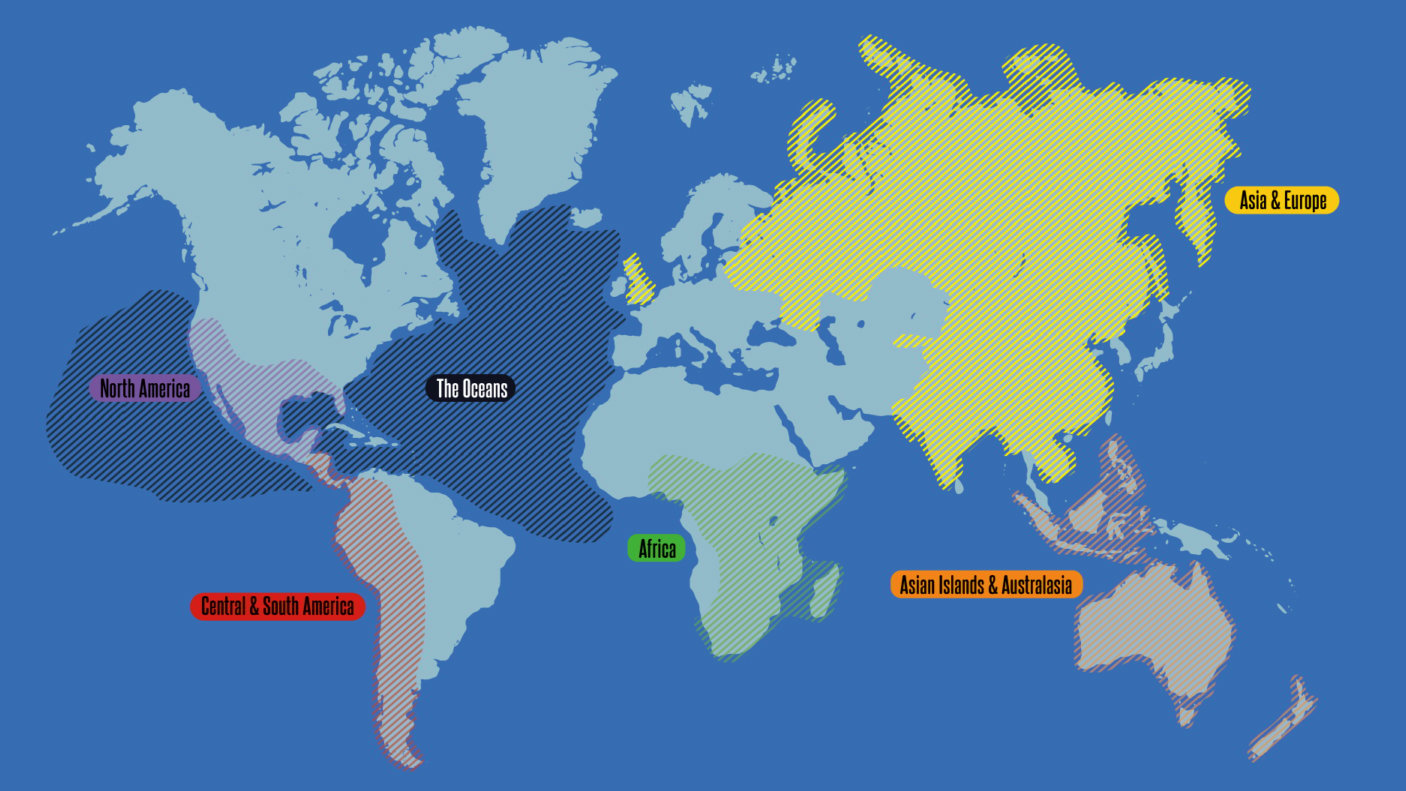

The Siamese crocodile can only be found in Southeast Asia, and many of today’s remaining Siamese crocodiles reside in the Mekong River Basin and Cambodia’s wetlands. They live in freshwater areas like rivers, lakes, swamps, marshes, and streams, preferring sloping areas surrounded by forests. Though they aren’t an aggressive species, they are very territorial when it comes to their homes. To mark their territory, they’ll slap their heads against the water and snap their jaws, warning nearby animals that they better find another place to hang out if they know what’s good for them.

Because Siamese crocodiles aren’t really picky eaters, they are essential for population control in their ecosystems. By eating various prey species, they help to prevent the blockage of waterways and habitat destruction from overpopulation. When these big creatures create their large nests and burrows, they also help provide habitats for other animals. Without the Siamese crocodiles, these freshwater homes could be ruined from overpopulation and exploitation by land-dwelling animals.

EXTINCT

No reasonable doubt that the last individual has died

EXTINCT IN THE WILD

Known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity or as a naturalised population

CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

Facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the Wild

ENDANGERED

Facing a high risk of extinction in the Wild

VULNERABLE

Facing a high risk of extinction in the Wild

NEAR THREATENED

Likely to qualify for a threatened category in the near future

LEAST CONCERN

Does not qualify for Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, or Near Threatened

Threat #1

Threat #2

Threat #3